The Disparate Impact of Differential Privacy

TL;DR: The cost of differential privacy is a reduction in a model’s accuracy. Furthermore, the accuracy of DP models tends to decrease more on classes that already have lower accuracy in the original, non-DP model., i.e., “the poor become poorer.”

In the past several years, several methods of applying differential privacy to machine learning have been proposed. One main method is differentially private stochastic gradient descent. DP-SGD works by clipping gradients during training, adding random noise to the clipped gradients, and using the moment’s accountant technique to track how much privacy is lost over the course of training.

While employing DP-SGD increases the privacy of the machine learning algorithm, the cost of doing so is a reduction in accuracy. In “Differential Privacy has Disparate Impact on Model Accuracy”, Eugene Bagdasaryan and Dr. Vitaly Shmatikov demonstrate that in the neural networks trained using DP-SGD, the accuracy of differentially private models drops much more for underrepresented classes and groups.

“For example, a gender classification model trained using DP-SGD exhibits much lower accuracy for black faces than for white faces.”

They explain that this phenomenon occurs since DP-SGD amplifies the model’s bias towards the most popular elements of the distribution being learned and demonstrate empirically this effect for gender/age classification, sentiment analysis, and species classification.

Gender and Age Classification

For this experiment, the authors use the Flickr-based Diversity in Faces (DiF) and the UTKFace datasets. They create their training and test datasets by creating an imbalance in the skin colors represented. They use 29,500 images from the DiF dataset that have individuals of lighter skin tones and use 500 images from the UTK dataset that have individuals with darker skin tones to create the training set. They additionally create a 5,000-image training set that has the same skin tone split.

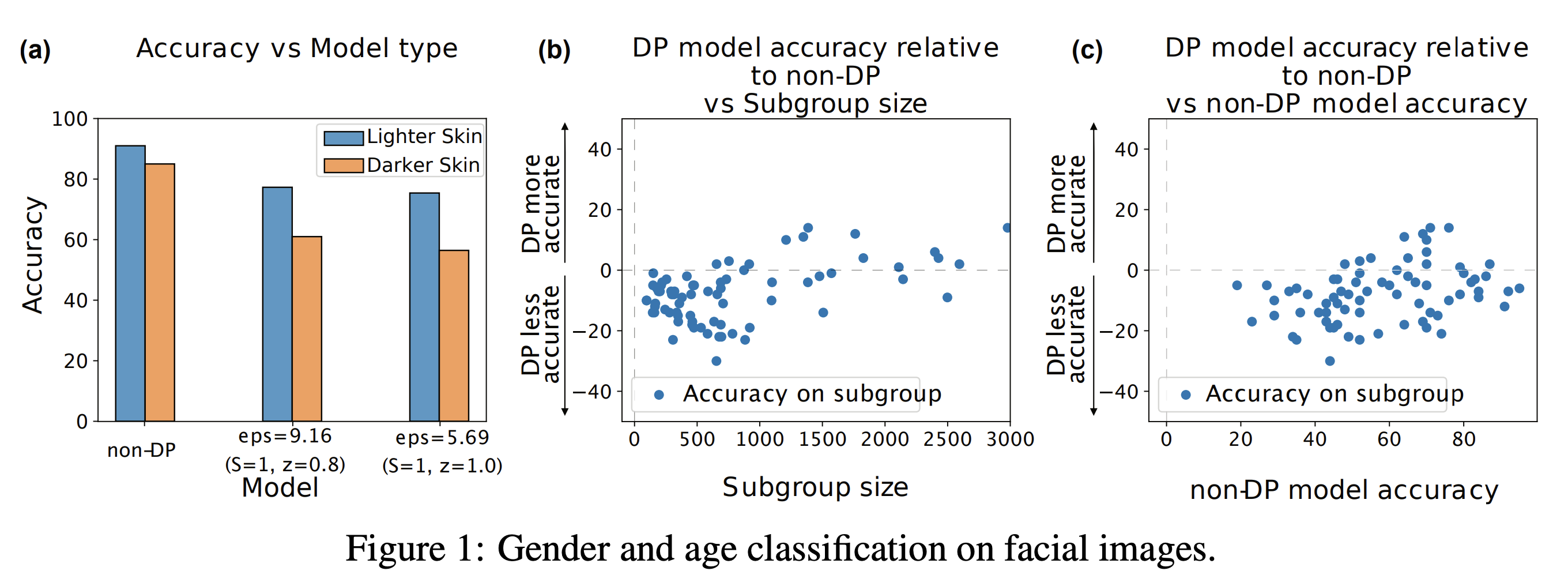

Figure 1(a) in the image below shows that the accuracy of the differentially private model drops more (vs. non-DP model) on the darker skinned faces than the lighter-skinned ones.

Figures 1(b) and 1(c) show their analysis on the accuracy of the DP model on small subgroups defined by the intersection of different attributes such as age, gender, and skin color. For these experiments, they randomly sample (without regards to skin color) 60,000 images from the DiF to train both DP and non-DP models. They then measure the accuracy across 72 different subgroups. Figure 1(b) shows that differentially private models are less accurate on smaller subgroups and Figure 1(c) shows the phenomena of “the poor get poorer”. In other words, it shows that classes that start with lower accuracy in the non-DP model suffer the biggest drops in accuracy as a consequence of applying DP.

Sentiment Analysis and Species Classification

For the the sentiment analysis task, the authors considered the setting of classifying Twitter posts from a corpus of African-American English as either positive or negative. The posts were labeled as either being written in Standard American English (SAE) or African-American English (AAE) and were assigned sentiment labels using standard heuristics. 60,000 SAE and 1,000 AAE were sampled for training and each set contained an even split of positive and negative samples (i.e., 30,000 positive SAE and 30,000 negative SAE).

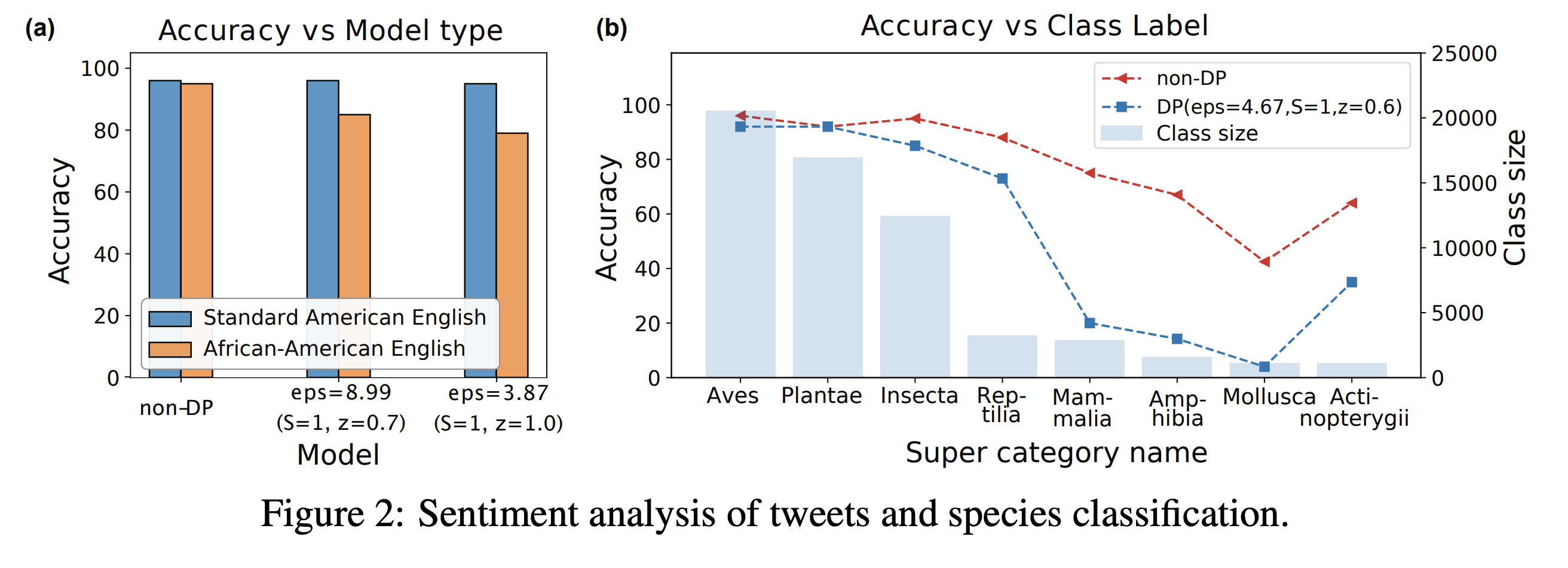

Figure 2(a) in the image below shows that all models learn the SAE subgroup (almost) perfectly but the accuracy of the AAE subgroups drops much more when differential privacy is applied.

For the species classification task, the authors use a 60,000-image subset of the iNaturalist dataset which contains hierarchically labeled plant and animal photos taken in natural environments. The task is to predict the top-level class that the plant/animal in the picture belongs to. Figure 2(b) in the image above shows that the differentially private model (almost) matches the accuracy of the non-differentially private model on the well-represented classes, but performs significantly worse on smaller classes. Additionally, the accuracy drop does not only depend on the size of the class. For example, they point out that the class Reptilia is relatively underrepresented in the training dataset, yet both the differentially private and non-DP models perform well on it.

Federated Learning of a Language Model

For this experiment, the authors used Reddit posts from November 2017 that were written by users who has written between 150 and 500 posts. The task considered was to predict the next word when given a partial word sequence. They implemented differentially private federated learning according to this paper.

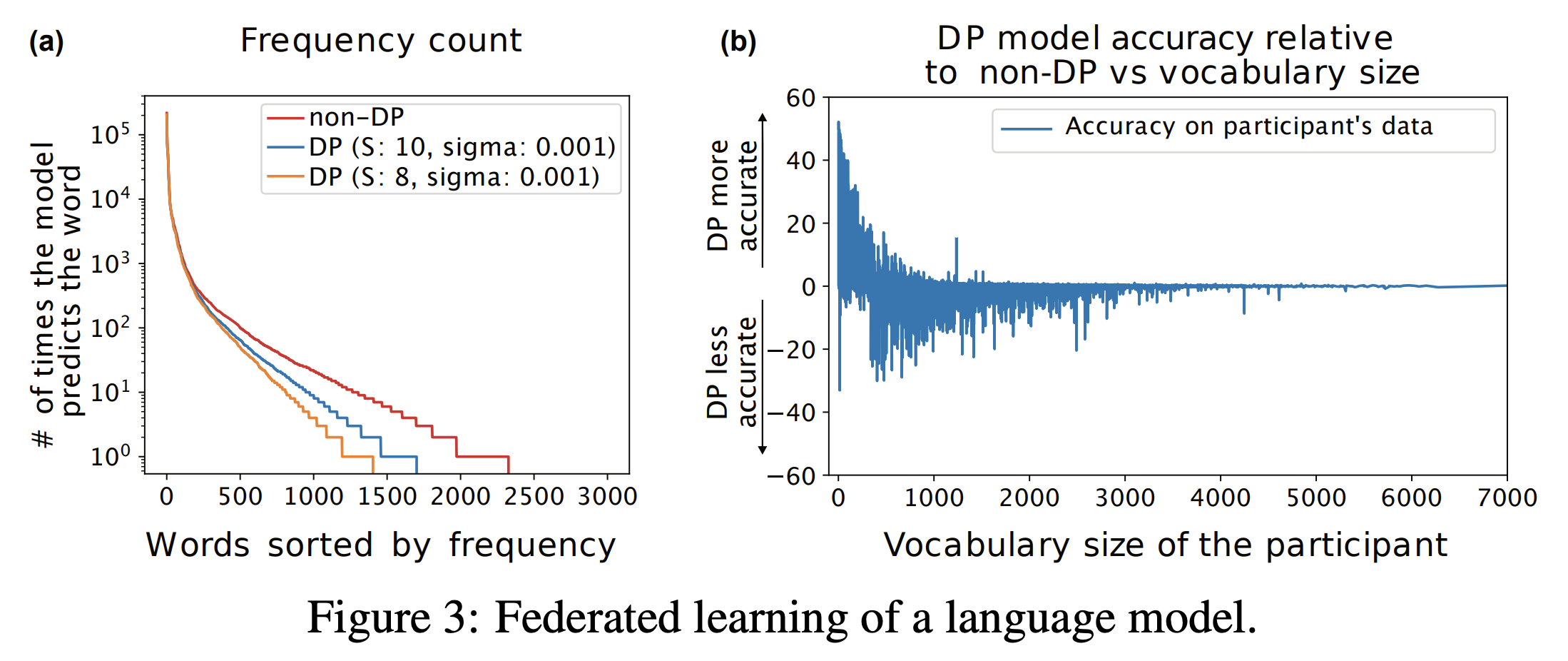

After training the models, both the differentially private and non-DP models achieved similar accuracy. Therefore, to illustrate the difference between the trained models that have similar test accuracy, the measure the diversity of the words the model’s output. Figure 3(a) in the image below shows that while all models have a limited vocabulary, the vocabulary of the non-DP model remains the largest.

The authors also compare the accuracy of the models on participants whose vocabularies have different sizes. Figure 3(b) in the image above shows that the differentially private model has worse accuracy than the non-DP model on participants with vocabulary sizes of 500-1,000 words and similar accuracy on large vocabularies. On participants with very small vocabularies, the differentially private model tends to perform much better. This is because the differentially model tends to only predict extremely popular words. Additionally, the authors note the following:

In federated learning, as in other scenarios, DP models tend to focus on the common part of the distribution, i.e., the most popular words. This effect can be explained by how clipping and noise addition act on the participants’ model updates. In the beginning, the global model predicts on the most popular words. Simple texts that contain only these words produce small update vectors that are not clipped and align with the updates from other, similar participants. This makes the update more “resistant” to noise and it has more impact on the global model. More complex texts produce larger updates that are clipped and significantly affected by noise and thus do not contribute much to the global model. The negative effect on the overall accuracy of the DP language model is small, however, because popular words account for the lion’s share of correct predictions.

Additional Works showing Disparate Impact of Differential Privacy

Several other works have been published showing this trend of DP-SGD disproportionately decreasing accuracy across different classes and subgroups.

- Privacy Risk in Machine Learning: Analyzing the Connection to Overfitting

- Poorly generalized models are more prone to leak training data

- Disparate Vulnerability: On the Unfairness of Privacy Attacks Against Machine Learning

- Attacks exploiting the leakage of training data disproportionately affect underrepresented groups

- Fair Decision Making using Privacy-Protected Data

- Resource allocation based on DP statistics can disproportionately affect some subgroups.

Solutions

In the past few years, several approaches to fixing the disparate impact of DP-SGD have been proposed. One popular technique is proposed in the paper Removing Disparate Impact of Differentially Private Stochastic Gradient Descent on Model Accuracy. In this work, the authors analyze the inequality in accuracy loss by differential privacy and propose a modified DP-SGD algorithm called DPSGD-F to remove the potential disparate impact of differential privacy on subgroups. DPSGD-F works by adjusting the contribution of samples in a group depending on the group clipping bias such that DP has no disparate impact on the group’s accuracy. In their experimental evaluation, they show how group sample size and group clipping bias affect the impact of DP in DP-SGD and how implementing adaptive clipping for each group helps to mitigate the disparate impact caused by DP in DPSGD-F. The authors additionally note that gradient clipping in the non-private context can improve the model robustness against outliers, however, examples in the minority group are not outliers and should not be ignored by the learning model – which they leave as a subject for future work.